(an extract from a text-in-progress)

Following the Soviet occupation in the 1980s, one of the earliest examples of overt propaganda in the range of imagery produced in Afghanistan and in the refugee camps in Iran and Pakistan was the representation of President Najibullah as a puppet of the Soviet Union. This bears a close – but not exact – correspondence to the propaganda posters produced by expatriate Afghans working out of Islamabad in the early 1980s. The posters, flyers, and even matchbook covers produced at that time were classic propaganda – pointed, bitter, angry cartoons and even more graphic realist images reflecting the alienation and history of the suffering of the Afghan people during this time.

A further reference to the possibility that these carpets may have been copied from propaganda posters is the inscription in English and Farsi along the lower edge of the first images of this kind to appear in collections in the west: “Published by the Ministry of Information Islamic Interim Government of Afghanistan.” The Interim Islamic Government of Afghanistan was a shaky coalition of opposition parties formed in 1989, and the faction led by Hekmatyar had been associated with the production of visual propaganda of this kind since the early 1980s. Thus we can suggest that the Najibullah carpets were produced in Pakistan no earlier than 1989/1990, in the period of political opposition to Najibullah’s continuing presidency following the exodus of Soviet forces in 1989.

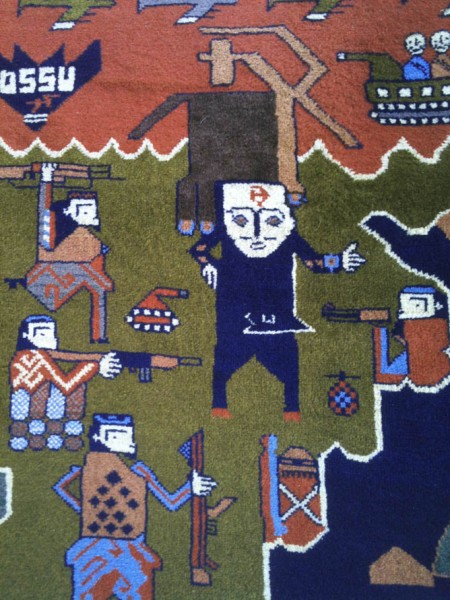

The figure of the President is depicted with hammer and sickle tattooed on his forehead being dangled over the map of Afghanistan by a giant hand descending from the North. This “hand of the Soviets” was surrounded by helicopters and bombs, the acronym USSR, and decorated with a distorted hammer-and-sickle emblem, making quite clear the message of the primary icon of the image. The secondary icons of the image are the depictions of the mujahideen in opposition, surrounding Najibullah and pointing their weapons at him. Further out, in the regions of the map identified (labelled) as Iran and Pakistan, the rugmakers depicted idyllic scenes of life before the invasion – Afghan nomads with their camel-trains, goats and sheep, and their portable houses. In this sense the complexity of this image is both political propaganda and an historical narrative projecting, perhaps, a return to the normality of the past.

Seen as propaganda, such imagery is as much oriented to a domestic audience as to the outside world. Yet these carpets made compelling viewing in the West – especially in the period of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet empire, when such aspects resonated with the tensions that were identified with the end of the Cold War. The first of these rugs to be seen and exhibited in the West was from the R. Neil Reynolds collection in Washington, in an exhibition titled “Pieces de la Resistance: Afghanistan’s war rugs”, curated by Tatiana Divens, in October 1993.

In the years that followed Najibullah being deposed (and later assassinated), during the disastrous civil war and the ascendancy of the Taliban, it appears the “puppet dictator” theme had lost its relevance, and rug designers and makers turned to other subjects and designs.

In the decade following September 11 2001, Afghanistan was once again “occupied” by the U.S.-led international anti-Taliban coalition formed to rebuild civil society and re-equip Afghanistan to defend its own territory. During this period the production of conflict carpets appears to have diminished, with the exception of the mass-reproduction of small tourist rugs, which are largely copies of themes developed during the Soviet era. Surprisingly, one of the most prolific of these is the imagery that continues to celebrate the exodus of the Soviet Army from Afghanistan in 1989. In my experience, there has been no production of an equivalent iconography that could be interpreted as anti-U.S., or anti-Western, especially given the make-up of the ISAF forces which took control of the country for the period since 2001.

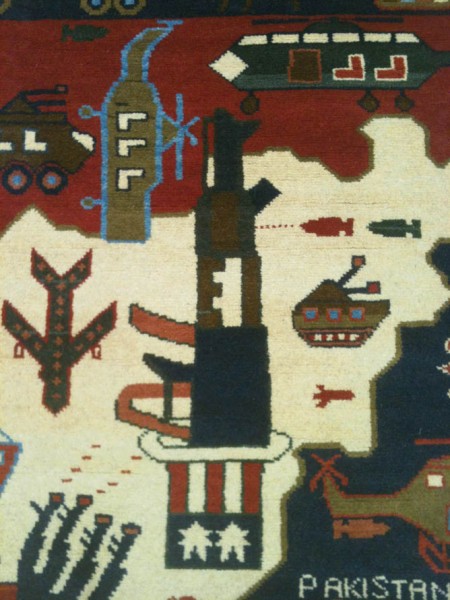

In about 2005 it appears that the makers of the original Najibullah carpets resumed production. This time, the primary icon of the image is the closest one might come to a response to Afghanistan’s changing circumstances and experiences. In the centre of the image, floating over the map of Afghanistan, one now finds a most curious emblem that is comprised of a Kalashnikov sitting inside an inverted “Uncle Sam” top hat. In the one hybridised emblem one sees both the archetypal symbol of the legacy of the military might of the Soviet Union, and a symbol of anti-imperialist politics globally, now embedded in the historical symbol of American imperialism. In these new rugs this ambiguous hybrid emblem is no longer surrounded by mujahideen, but by militaria of every possible kind. Equally, while the general style of these carpets is completely coherent with those of the Najibullah era, they have lost the specific historical references and narratives that once made its predecessors so distinctive.

And yet this new Soviet/U.S. icon has its own compelling affect. It is as if the designer/makers were searching for a new iconography that alludes to a cultural experience for an audience beyond that of the tourist market, or of mere propaganda, oriented to an indigenous audience. In this sense, these carpets are more like the rich and complex imagery of the narrative carpets of the 1980s. The montage effect – whereby the merger of two icons synthesises a third order of meaning – signals a complex order of intention on the part of its designer/makers. To my reading, these conflict carpets are more like that found in early Social Realism that the propaganda generated by contemporary forms of psychological warfare. It would seem that by combining the familiar symbols of the two world superpowers, the makers are signalling both a sense of the perpetual crisis besetting their country of origin, and a sense of their subjecthood, in a state of being perpetually dominated by the world outside their borders.

Leave a comment