The recent suite of retrospective exhibitions of the work of Alighiero Boetti at the Museo Reina Sofia, the Tate Modern, and the Museum of Modern Art, plus another at the Fowler Museum at UCLA has triggered substantial catalogues, monographs and other publications, plus reviews and commentary. All of these have, to greater or lesser degree, repeated and elaborated a set of myths in relation to his outsourced embroideries, kilims, and carpets produced in Afghanistan and Pakistan between the years 1972 and 1994. The following abstract summarises an online essay published by the Melbourne University Art History journal EMAJ, in which I pose a counter-argument to the conventional account now established in the Boetti literature.

A tournament of shadows: Alighiero Boetti, the myth of influence, and a contemporary orientalism

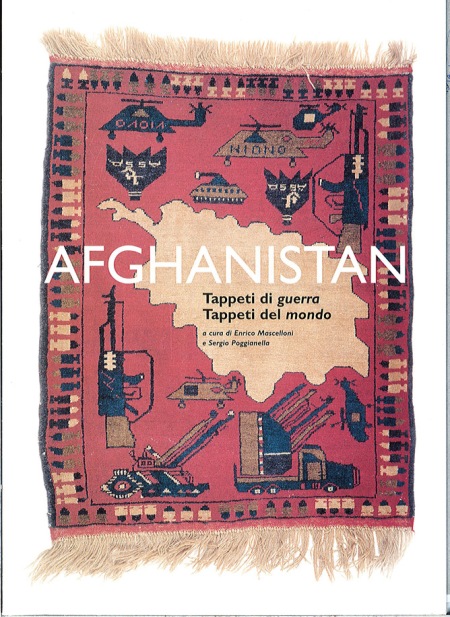

This paper examines the evolution of the historical and theoretical literature that has developed about the work of the avant-garde Italian artist Alighiero Boetti produced in Afghanistan from 1971 until 1994. Characterised by a set of interrelated cultural and historical fictions, I propose that this collective narrative has evolved to constitute a contemporary orientalist mythology. This is particularly evident in the literature following his death in 1994, and most recently in anticipation of his retrospective exhibitions in the Museo Reina Sofia, the Tate Modern, and the Museum of Modern Art in 2011–12. Prior to his death, the literature on Boetti primarily took the form of catalogue essays, journal articles and biographies. These drew heavily on a small number of interviews conducted with the artist, plus accounts and memoirs given by his wives, partners, and curatorial collaborators. Since his death, the literature has proliferated, and today a greater emphasis is placed on a growing number of secondary authorities. Recent monographs, catalogue essays, and auction house texts draw heavily on the anecdotal accounts of his agents and facilitators, as well as his familiars, employees and archivists. In exploring what I describe as the mythologies informing the contemporary reception of his work, I examine the claims of his influence over the distinctive indigenous genre of Afghan narrative carpets which were produced both within Afghanistan as well as by diasporic Afghans in Iran and Pakistan in the years following the 1979 Soviet invasion until the present. The attribution of political intent in the later Boettis, whether attributed to the artist or on the part of his agents, is a recent invention worthy of challenge. Finally I argue that such interpretations of his attitudes and practice might be described as a form of late orientalism, a mode of representation occurring through the appropriation of tradition and the projection of cosmopolitan values and avant-garde practices onto this most conflicted and exoticised cultural context of the contemporary era.

You can download the essay by going here: